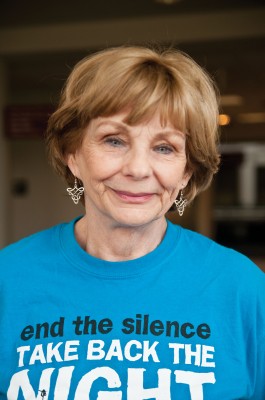

Suzanne Scott has been the director of the women and gender studies program at George Mason University since 2009. She became a teacher after successful careers as a writer, business owner and mixed-media artist. No matter what she’s doing, the issues of social justice and equality always factor into her work.

Scott grew up in Raleigh, N.C. Her childhood shaped the way she approaches race and class.

“Even when I was four and five years old I was worried about the racial issues in the south,” Scott said. “When we would go out in public, I would see how differently African-Americans were treated. It was different from what I knew it to be like at home.”

Although Scott came from, in her own words, a “good, liberal, progressive-type family,” she said uncovering and exploring her own and others’ prejudices has been a lifelong journey. While running a communications business, Scott began freelance writing about social issues.

“The real ‘a-ha moment’ for me was when I fell in love with a woman,” Scott said. It was then that two other issues became central to her work: gay rights and feminist theory.

In 2000 she decided that she was old enough to do what she truly wanted, which was to teach. She accepted a position at the New Century College.

Today she also co-chairs the LGBTQ Campus Climate Task Force. As the director of the women and gender studies she works to coordinate the two programs.

Scott has always been out to her colleagues but chooses to tell her students on a need-to-know basis — like when her teaching partner introduced herself to their class by describing her family and her husband.

“I said, ‘Well, if she’s talked about being married, I’m going to tell you about who I’m with and can’t marry,’” Scott said. “I’ve been with my partner for 30 years. We have four children, six grandchildren and a dog named Lola.”

After class a student told Scott that she had taken four classes with her and never suspected that she was gay.

Her partner, Lynne Constantine, is a professor in the School of Art. In Virginia, same-sex couples do not have the right to marry. Because Mason is a public institution, it does not extend the benefits of married couples to domestic partnerships, an issue that is important to Scott.

However, Scott doesn’t want her sexual orientation to define her. Like being a teacher, artist and mother, it is just another descriptor of her life.

“I can do more to change attitudes because it isn’t the first thing someone would suspect about me,” she said.

Flora Crater, an alumna of George Mason University, spent over three decades battling for women’s rights and blazing trails for female candidates in Virginia politics. She lobbied Congress for passage of the yet-to-be-ratified Equal Rights Amendment, which guarantees equal rights under the U.S. Constitution, ran for Virginia lieutenant governor, for the U.S. Senate and founded the Virginia chapter of the National Organization for Women.

Crater first entered politics in 1952 when she worked with the Falls Church school board, later becoming a regular at Fairfax County Democratic Committee meetings.

Crater first entered politics in 1952 when she worked with the Falls Church school board, later becoming a regular at Fairfax County Democratic Committee meetings.

However, it wasn’t until the Equal Rights Amendment came up for a vote in Congress that she was thrust into national politics.

From 1971 to 1972 she headed a citizen group dubbed “Crater’s Raiders” that played a central role in the effort to pass the amendment. Crater’s group met every Wednesday morning in the House or Senate cafeteria to decide which legislators to lobby. Crater’s followers would then fan out, hounding congressmen, passing out pink flowers and recording information about the lawmakers’ voting intentions on pink tally sheets. They were “one of the most powerful and unlikely pressure groups that Congress has ever seen in operation,” said Washington Star White House correspondent Isabelle Shelton in an article at the time of the ERA lobbying effort.

In 1976 Crater founded the Virginia Almanac of Politics, a bi-annual publication that tracks Virginia elections, demographics and political trends. Mason public and international affairs professor Toni-Michelle C. Travis took over the publication, which is now published by Mason, after Crater’s death in 2009.

Crater’s political activism resulted in numerous accolades over the course of her career. A joint resolution passed by the Virginia House and Senate in 1997 commending Crater for her activism attests to her legacy in Virginia politics. “Flora Crater stands as an example of the difference one person can make for the good of many people,” then Virginia Delegate L. Karen Darner (Dem, 49) said.

She also received an award from the Fairfax County Human Rights commission, as well as the Barbara B. Knight Distinguished Alumni Award from Mason.

Crater earned a bachelor’s degree in government and politics from Mason in 1981. She was also around when the women and gender studies program was created at Mason.

“Flora wanted to be a women’s studies major,” Travis said. “[She] was quite a character.”

Crater was born in 1915 in Costa Rica. She grew up in Orange, Va., where she also passed away at the age of 94.

Comments